An 11-minute interview conducted by Stacy Hinck and Zoe Meras, students of Dr. Brantley Gassaway's class History of Religion in America at Bucknell University. Their questions are well-thought out and generate a great discussion about:

* how religion and the environment intersect

* Lutheran theology and biblical interpretation influenced by and addressing care of Creation

* the rationale for Christians being advocates for ecojustice issues

* the model of public theology provided for us by Jesus' ministry

* the connection between climate change awareness and preaching

* the calling to initiate a "green" civil rights movement.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NQ7KDYbVyFw

Features sermons, essays, movie and book reviews, creative writing and ecotheological reflections.

Monday, December 29, 2014

Monday, December 22, 2014

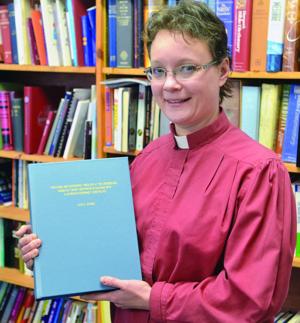

Pastor brings ecology to art of preaching: article on Leah Schade's upcoming book

http://www.dailyitem.com/news/pastor-brings-ecology-to-art-of-preaching/article_01c09a98-88b0-11e4-809d-b741c80dc2a0.html

Pastor brings ecology to art of preaching

by Evamarie Socha

The Daily Item

- Posted on Dec 20, 2014

LEWISBURG — A Valley pastor has blended two passions, preaching and nature, for a ministry that focuses on the spiritual aspects of caring for the environment and a book that will show other clergy how to do the same.

The Rev. Dr. Leah Schade, 43, of Milton, just finished her book, “Creation/Crisis Preaching: Ecological Theology and Homiletics,” which will be published and released by Chalice Press next fall.

The book is a reworked version of her dissertation, which she successfully defended in August 2013 for her doctoral program at the Lutheran Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. Schade graduated in May.

Schade leads United in Christ Lutheran Church in Lewisburg, now in its fourth year, and founded the Interfaith Sacred Earth Coalition of the Susquehanna Valley. Many people here know Schade from among leaders of a grass-roots effort that helped bring an end to a proposed tire-derived fuel plant in Union County.

“The work in that was incredibly helpful” to the book, she said, as an example of how as a faith leader one engages the public. “How do you talk to constituents who are different from your religion or not religious at all? Where can we find the bridges that enable us to do this work together?” Her dissertation focused on preaching and ecological theology, and “I knew I wanted to turn it into a book for more mainstream audiences,” she said.

The seeds for the blend of church and ecology were planted when Schade was a child. Her father was a landscape designer, and the family had a hunting camp in Huntingdon County, where they spend considerable time, she said. Schade recalled hunting and fishing with her father and spending countless hours in the local creeks, just immersing herself in nature.

“There were a couple formative experiences that were defining for me as a young person,” she said, “seeing many natural places destroyed by development, pollution and feeling helpless as a kid, thinking there is nothing you can do.”

Schade’s first congregation was in Media, where she started an ecology ministry. Also during that time, she decided to get a doctorate in preaching.

“Through the application process, it became apparent this is where I need to focus, this is what is missing in homiletics,” or the art of preaching, she said. “I wanted to be someone to help pastors learn how to preach with the voice of Earth at the table.”

With the tire-burner proposal, “the threat to public health was really a unifying factor there,” Schade said. “We had a great time with people working on that and learning social movement theory,” that is, what is the role of religion in these movements?

Taking cues from the civil rights movement, Schade calls such ministry “a green civil rights movement, and pastors need to be part of it. ... From my perspective, one of the things pastors are called to do is confront the powers that are oppressive.”

Schade also is an adjunct professor at Lebanon Valley College in Annville, where she’s teaching a course on ethics.

The Rev. Dr. Leah Schade, 43, of Milton, just finished her book, “Creation/Crisis Preaching: Ecological Theology and Homiletics,” which will be published and released by Chalice Press next fall.

Schade leads United in Christ Lutheran Church in Lewisburg, now in its fourth year, and founded the Interfaith Sacred Earth Coalition of the Susquehanna Valley. Many people here know Schade from among leaders of a grass-roots effort that helped bring an end to a proposed tire-derived fuel plant in Union County.

“The work in that was incredibly helpful” to the book, she said, as an example of how as a faith leader one engages the public. “How do you talk to constituents who are different from your religion or not religious at all? Where can we find the bridges that enable us to do this work together?” Her dissertation focused on preaching and ecological theology, and “I knew I wanted to turn it into a book for more mainstream audiences,” she said.

The seeds for the blend of church and ecology were planted when Schade was a child. Her father was a landscape designer, and the family had a hunting camp in Huntingdon County, where they spend considerable time, she said. Schade recalled hunting and fishing with her father and spending countless hours in the local creeks, just immersing herself in nature.

“There were a couple formative experiences that were defining for me as a young person,” she said, “seeing many natural places destroyed by development, pollution and feeling helpless as a kid, thinking there is nothing you can do.”

Schade’s first congregation was in Media, where she started an ecology ministry. Also during that time, she decided to get a doctorate in preaching.

“Through the application process, it became apparent this is where I need to focus, this is what is missing in homiletics,” or the art of preaching, she said. “I wanted to be someone to help pastors learn how to preach with the voice of Earth at the table.”

With the tire-burner proposal, “the threat to public health was really a unifying factor there,” Schade said. “We had a great time with people working on that and learning social movement theory,” that is, what is the role of religion in these movements?

Taking cues from the civil rights movement, Schade calls such ministry “a green civil rights movement, and pastors need to be part of it. ... From my perspective, one of the things pastors are called to do is confront the powers that are oppressive.”

Schade also is an adjunct professor at Lebanon Valley College in Annville, where she’s teaching a course on ethics.

Monday, December 15, 2014

Advent Sermon: Embracing New Life in Darkness

Sermon Series: Learning to Welcome the Dark, Part Three

The Rev. Dr. Leah Schade

Dec. 14, 2014

Isaiah 7:13-17; Psalm 139:1-18; Luke 1:26-38

13 For it was you who formed my inward parts; you knit me together in my mother’s womb.

14 I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.

50 His mercy is for those who fear him from generation to generation.

God has not abandoned us. God is at work as much now as in the beginning of our dark-shrouded world, as when God’s people cried out for justice and mercy from the depths of the biblical texts. The God of Mary’s womb, and the God of Jesus’ tomb – both places of darkness – is our God: the God of our broken bodies and hearts and communities who comes to bring healing and new life in the darkness. Put your hands on God’s strong shoulders, listen for God’s voice guiding you in the darkness. And take your first shuffling step. Amen.

The Rev. Dr. Leah Schade

Dec. 14, 2014

Isaiah 7:13-17; Psalm 139:1-18; Luke 1:26-38

A few

weeks ago I did a children’s sermon where we talked about the phases of the

moon, and I handed them a calendar that showed what phase the moon would be in

during this month. Starting today, that

glowing orb in the sky is waning toward “new moon,” which will be on Dec. 22,

when the moon’s light disappears. Interestingly,

Dec. 21 is Winter Solstice – longest night of the year. So the darkest night of the year will have

not have any moonlight either. This is a

dark time.

We

sometimes hear people use that phrase to describe their lives or the state of

our world. If someone says “this is a

dark time” – what do they mean? I posed this

question on Facebook and invited people to respond. The question sparked nearly 30 comments. Answers I got were: a valley of grief, tyranny and destruction running rampant, confusion

and fear,

lack of knowledge and wisdom. In movies, whenever a war or battle is about to start, someone says

"dark times are coming." It’s a time of negativity, injustice, oppression, overwhelming

challenges, and depression. For some,

this time of year reminds them of losses they have suffered, especially loved

ones who have died, with whom they are no longer able to share the

holiday. When people say “it’s a dark

time,” it can mean what is absent - not much hope or joy. | Lester Johnson, Three Transparent Heads, 1961 |

By these

counts, I think the argument can be made that we are in a “dark time.” Racial tensions in our country are as high as

I’ve ever seen. We hear news about rapes

on college campuses, threatening the safety of our daughters. There are debates about the value of using

torture as a means by which to extract information from our enemies. News about worsening pollution and climate

disruption from fossil fuel extraction processes. As a friend said in one of her responses to

my post: “Watch CNN or the local news and it paints

the picture of darkness. Current affairs that we are confronted with daily: Police

Brutality, ISIS, War, School Shootings,” the list can seem endless. These are, indeed, dark times.

But as we’ve learned in these past few weeks on this sermon series

about learning to welcome the dark, it’s important to unpack the stereotypes

people have about darkness. Especially

since people with darker skin are unconsciously or even consciously demonized

simply for their skin’s pigmentation. And when it comes to the feelings of

anger, grief and depression that arise in response to these personal, national

and global injustices, let’s not push too hastily for people to “get over it,”

to swallow their pain and anger and “move forward,” as the saying is so often

reiterated.

Because

as Barbara Brown Taylor reminds us in her book, Learning to Walk in the Dark, “The best thing to do when you are

flattened by despair is to spend time in a community where despair is daily

bread. The best thing to do when sadness

has your arms twisted behind your back is to sit down with the saddest child

you know and say, ‘Tell me about it. I

have all day.’” (Taylor,

Barbara Brown, Learning to Walk in the Dark,

HarperOne, New York, NY, 2014; 86). But we have

to do this without expecting all this to magically cheer us up and whisk us out

of our dark emotions. By listening to

their words, hearing their stories, and holding those powerful, violent

emotions as best we can, we are at least acknowledging that, yes, this has

happened, and it is worthy of healing.

But of course, many would disagree. You may have noticed the kind of rhetoric

that has arisen in response to these events, the kinds of insensitive, offensive remarks jumping off of blog posts and blurted by political

pundits that seek to blame the victims, downplay the seriousness of the issues,

and divert our attention from the work that needs to be done. Our culture basically pushes two

options for us in the face of these massive injustices: fight or flight. Toss nasty verbal grenades into the fray, or

turn away and shop shop shop for the best holiday deals.

It is understandable to react to these strong feelings of those

who cry out against injustice with either dismissive acidity or detached

numbness. Because some of us have never experienced this kind of

suffering. We build walls between us and those who suffer a thousand

micro-aggressions over the course of their lives due to their skin color. Between us and the ones whose suffering is

distanced from us. Between us and the

woman who has been raped. We cannot bear such suffering, so we express

outrage that such intensity of pain is even voiced. Yet these words of

frustration and rage are found throughout the Bible, in the Psalms, in the

mouths of prophets like Jeremiah and Habbakuk who says: “Why

do you make me see wrongdoing and look at trouble? Destruction and violence are

before me; strife and contention arise.” (Habakkuk 1:3)

Here’s what we must do with those enraged by Ferguson, and those

standing in oil-slicked soil on their farms, and those whose bodies have been

abused and assaulted: we must listen to them, and hear them in the

context of prayer. We all know we live

in a world marked by violence and revenge - wouldn’t it be prudent to put those

feelings into a prayerful context? Wouldn’t it be wise to invite God into

these feelings?

That’s

just what Mary does in the Gospel of Luke. Mary was a woman who lived in “dark

times.” Because the

days leading up to Gabriel’s Annunciation to Mary were filled with many of the same

things identified by the Facebook observations. Her people were oppressed by the Romans and

despised in much the same way as people of color are in this

country. They lived under military

occupation and the soldiers often used violence in their patrols of the

villages and cities. Diseases were

common, poverty was nearly universal outside of the homes of the wealthy elite,

and crime was a constant. Hopelessness

and depression could easily settle into one’s heart, and even take hold of an

entire community. All this could lay open a person’s mind to the creeping suspicion

that perhaps God has finally abandoned us, left us to our own devices, given up

on us.

The world holds its collective breath, waiting to see if and how

God will respond. Will God punish us for

these feelings or mutely turn away?

Neither. God chooses a third way. God listens and responds. God responds by effecting a transformation in

the darkness. Despite all of the

negative stereotypes about darkness, Mary instinctively understood that God

works in darkness differently than in light, but God still works in those dark

places. It is within Mary’s womb, as

dark a place as can be found, that the Messiah is conceived and grows. There in the secret, dark place of a young unwed

teenage girl’s shame – there you see, is Mary’s God, the God of our raped

daughters, the God of our murdered sons, the God of our desecrated earth. This is the God who sees that things must change, and creates in her a

future that causes Mary to burst forth in song:

“My soul doth magnify the Lord and rejoices in God, my savior! For he has looked with favor on the lowliness

of his servant. Surely, from now on all

generations will call me blessed.”

In what

ways might Darkness be trying to effect a transformation in you, in us? What voices are we supposed to hear in the

Darkness? Whose hands can we reach

for? Especially during this period of waning

moon and approaching winter solstice, what Taylor calls “endarkenment,” let’s

not be too quick to run to “the light” and miss what Darkness is trying teach

us, trying to dismantle in our individual and collective egos.

The

Darkness is trying to show us that we can do better, that we need to reach out

for the hands and shoulders of God’s sons and daughters - no matter their skin

color, sexual orientation, culture or economic level – and see them as having

inherent dignity, value and worth. The

Darkness is urging us to sharpen our senses to God’s created world and

recognize that our earth and its precious waters and biotic communities have

inherent dignity, value and worth.

So how do

we take those first, shuffling steps into the darkness? This

afternoon some of us will be taking gift bags and singing carols at Country

Comfort Assisted Living. We will be

going to what some people think of as a “dark place,” where the elderly wait

for the final shroud of death to enfold them, a place where few people go to

visit because it’s uncomfortable, and they do not want to be reminded of their

own mortality. But we will go and see

that even in that dark place, new life grows in unexpected ways.

Two days ago I went to another place that people might call “dark.” I went to Haven Ministry, the homeless shelter

for our tri-county area. Few people

would want to be there, a place where poverty throws its victims, where

domestic violence tosses its abused women and children, a place where people

only go as a last resort. I only went because I was sent there with the gifts

bought by our youth with money from our Rich Huff Fund. So I arrived with clothes, a toy and some

diapers for a 5-week-old infant who was there with his mother. I don’t know what her circumstances were, but

I could imagine the pain and humiliation she had endured, the hopelessness she

must have experienced, the “darkness” that surrounded her. But I asked if I could see the child – and she

took me back to her little room. There

on the bed the little baby boy was sleeping, as perfect and holy a child as I’ve

ever seen. New life in this place of

darkness.

In a few minutes, I will hold Laylanya and Koda in my arms and stroke

their soft hair with the baptismal waters, a reminder of the dark birth waters

of our planet, the dark waters that pillowed them in their mother’s womb. And I pray that when the day comes when they

feel lost and abandoned in the darkness, they will be reminded of the words from

Psalm 139:

Even the darkness is not dark to you; the

night is as bright as the day, for darkness is as light to you. 13 For it was you who formed my inward parts; you knit me together in my mother’s womb.

14 I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.

God

is calling us in the dark to listen and learn and lend a hand even more at this

difficult time. Because, as Mary reminds us, God is at work in ways that are

not immediately visible to us, but are nevertheless powerfully moving among us:

49 For the Mighty One has done great things for [us],

and holy is his name. 50 His mercy is for those who fear him from generation to generation.

God has not abandoned us. God is at work as much now as in the beginning of our dark-shrouded world, as when God’s people cried out for justice and mercy from the depths of the biblical texts. The God of Mary’s womb, and the God of Jesus’ tomb – both places of darkness – is our God: the God of our broken bodies and hearts and communities who comes to bring healing and new life in the darkness. Put your hands on God’s strong shoulders, listen for God’s voice guiding you in the darkness. And take your first shuffling step. Amen.

Thursday, December 11, 2014

An Advent Sermon Preached as the Character of Darkness

Learning to Welcome the Dark, Sermon Series, Part Two

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade

December 7, 2014

Matthew 1:18-25

Watch the video of this sermon: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8HikRTIF2e8

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade

December 7, 2014

Matthew 1:18-25

Watch the video of this sermon: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8HikRTIF2e8

Some call me

Nyx, the daughter of Chaos. Some call me la noche, the night. You may

call me Darkness. I am the bringer of sleep; I usher in the

hush of slumber. I was with God from the

beginning, choshek, covering the face of the

deep out of which God burst forth with all of Creation. I was given equal time with my twin sibling Light. In my body I hold the stars and moon. Within me are the hidden places where life begins. I am the keeper of sacred secrets.

I touch each

of you every night with my soft caress, gently pulling you down to your

pillow. You may think that your brain shuts

itself off when I pull the curtain over your eyes, but what I see is something

very different. I watch your neural

cells clean away the toxins of all your thinking during the day. I see your body healing itself, all the

organs and systems realigning to the order set for them by God’s hand.

And yet I am

given so little time to do my work with you.

You chase me away more and more with your addiction to light. How I long to embrace you and fill you with my

life-giving, life-restoring power. But

every night you poke holes in me with the little red lights from your machines,

the blinking dots by your bedside, the flickering screens that confuse your

brain and damage your body’s ability to rest. You pride yourself on your ability to fight

me, to resist my pull over you. But you

only hurt yourself when you refuse the gift of sleep I offer you.

You think

you must push me away. But what you do

not realize is that I am the escort of God’s angels to you. Angels are the messengers of God, and they

work best when you sleep. After your

brain mops up all those stress chemicals in your brain, sweeping away the

detritus of your mind, only then is there room and space for the dreams. The angels bring you the dreams that contain

God’s messages to you.

I remember a

night many moons ago when I was the angel’s escort to a man named Joseph. This man had always fought against me. He did not like darkness. He slept with a candle lit in his room every

night. He preferred daylight when he

could see to pick up his carpenter’s tools and work the wood of his trade. He was a strong man with splintered and rough

hands. But his heart was gentle and

kind, sanded down smooth by the love of his mother and father.

All his life

they had faithfully brought him to synagogue, taught him the Torah, and on the

evenings of the Shabbat, when I have the joy of bringing the day of rest, they

gathered as a family to keep this holy commandment. God’s Law, God’s history with the people, the

stories gathered and retold over centuries of God’s saving love for them –

these are what shaped and refined the wood grain of Joseph’s character week by

week, month by month, year by year. His

mind and his morals were as sturdy as the furniture he and his father fashioned

in their shop, glistening with the fine oil they applied to the surface of the

wood to make it shine.

It was this

shine that caught the eye of the young girl who would one day become his

betrothed. Mary liked the sureness of

Joseph, his dependability, his steadfastness.

She liked the idea of being married to a man who could provide for her

and her children – not just the means to raise a family, but the faith in God

that would keep them joined to their people and their history, as sure as the

legs of the tables he made were fitted snug to the top, supporting it without

fail.

And Joseph

was drawn to this young girl who seemed to have a wisdom from depths he could

not fathom. She thought deeply and

looked at you with eyes that saw beyond your own thoughts. Certainly she was unlike the other young

women who were suggested to him as prospective mates. Mary was a woman who welcomed me, invited me

in willingly every night. She needed no

candle. She made me her friend, shared

her prayers with me in her under-the-blanket voice.

It did not

surprise me at all when I learned I was to escort an angel to her one night. He came with the message that the Messiah was

to be born to her, Mary. The Hope of the

world had found the one in whom he should incarnate. I watched her closed eyes move rapidly beneath

her lids as she spoke to the angel in her dream, wondering how she would

conceive if she and Joseph were not yet married. You may wonder the same thing. All I can tell you is – I am the keeper of

sacred secrets. Within me are the hidden

places where life begins.

She could have

waited to tell Joseph until the roundness of her belly began to show, but she

did not. She could not. She loved Joseph, trusted him with her secret

as much as she trusted me.

But Joseph

does not like mystery. He likes surety,

security. This news was heart-rending for him.

Night after night I tried to bring sleep to Joseph, to soothe him. But no sooner had he laid his head into my

bosom did he bolt upright again, pace his room, murmur to himself, pray into my

hands and ask for God’s mercy. By day

the dark circles under his eyes grew deeper.

His work in the shop became shoddy and he injured himself because of his

tiredness.

He knew that

by rights he could have dragged Mary into the street to have her stoned for

carrying a child that was not his own.

But as I said, he was an honorable man.

He resolved to quietly end their betrothal and leave her to her parents

who would certainly send her away, such was the shame she had brought to them. It was that night after he had made that

decision, when I brought the angel to Joseph.

He was so

exhausted by then, he could no longer resist my pull on him, and he laid down

to sleep after lighting his familiar candle.

I brought in the night breeze to extinguish it just before I escorted

the angel to his bedside. He came with

the message that the child growing in Mary was the Messiah and that he should

not be afraid to take her as his wife. I

watched Joseph’s closed eyes move rapidly beneath his lids as he spoke to the

angel in his dream, wondering how he would withstand the shame, the ridicule of

their neighbors. You may wonder the same

thing. All I can tell you is - within me

are the hidden places where life begins.

I am the keeper of sacred secrets.

And that night Joseph rested better than he had his whole life. From that night on, Joseph and I became good

friends. He learned to trust me. And I would bring the angel to him many more

times with even more important messages.

Sunday, November 23, 2014

Eschatology and Ecofeminist Theology: The Challenge of Preaching the "New Creation" in a Time of Environmental Crisis

We're approaching texts in the Sundays of Advent ahead that have to do with "end times." Last year I presented a paper hosted by Northeastern Seminary in October 2013 on how to preach on this theme from an ecofeminist perspective . Contact me for the full paper (leave a comment below). Here is an intro to the summary:

For preachers, eschatological themes are anticipated with nearly as much enthusiasm as dental check-ups. “The end of the world . . . again,” quipped one pastor at a pericope study I once attended as we tackled once more the images of the end-times that proliferate in the last Sundays of Pentecost and the first Sundays of Advent. This sarcasm perhaps masks a deeper unease about the real fears alluded to in passages such as Revelation 21:1-5 whose warnings of impending cosmic upheavals ricochet sharply off contemporary headlines about war, natural disasters, and strange “signs” that warn of dire days ahead.

Add to this the disconcerting news about species extinctions, the climate crisis, football-field-lengths of forests disappearing by the hour, and extreme forms of energy extraction, and the task of preaching “good news” in the face of seemingly immanent ecological doom can feel overwhelming to pastor and congregation alike. Especially for the preacher, the dual temptations to either legalistically preach about “saving the earth” or to irresponsibly encourage waiting passively for a messianic solution can lead to an “apocalyptic either/or logic—if we can’t save the world, then to hell with it. Either salvation or damnation,” as Catherine Keller observes

To read the full post: http://blog.nes.edu/bid/189257/eschatology-and-ecofeminist-theology-the-challenge-of-preaching-the-new-creation-in-a-time-of-environmental-crisis?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social&utm_content=2472027

For preachers, eschatological themes are anticipated with nearly as much enthusiasm as dental check-ups. “The end of the world . . . again,” quipped one pastor at a pericope study I once attended as we tackled once more the images of the end-times that proliferate in the last Sundays of Pentecost and the first Sundays of Advent. This sarcasm perhaps masks a deeper unease about the real fears alluded to in passages such as Revelation 21:1-5 whose warnings of impending cosmic upheavals ricochet sharply off contemporary headlines about war, natural disasters, and strange “signs” that warn of dire days ahead.

Add to this the disconcerting news about species extinctions, the climate crisis, football-field-lengths of forests disappearing by the hour, and extreme forms of energy extraction, and the task of preaching “good news” in the face of seemingly immanent ecological doom can feel overwhelming to pastor and congregation alike. Especially for the preacher, the dual temptations to either legalistically preach about “saving the earth” or to irresponsibly encourage waiting passively for a messianic solution can lead to an “apocalyptic either/or logic—if we can’t save the world, then to hell with it. Either salvation or damnation,” as Catherine Keller observes

To read the full post: http://blog.nes.edu/bid/189257/eschatology-and-ecofeminist-theology-the-challenge-of-preaching-the-new-creation-in-a-time-of-environmental-crisis?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social&utm_content=2472027

Sunday, October 26, 2014

Lutheranism - The Good, The Bad, and the Grace

Sermon for Reformation Sunday

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade, PhD

United in Christ Lutheran Church, Lewisburg, PA

Oct. 26, 2014

Some of us have been Lutheran since the day we were baptized. Some became Lutheran later in life or have just recently become Lutheran. But even if you are not Lutheran, every one of us has had our

lives shaped by the hand of Martin Luther and his legacy, which we celebrate

today. Let me explain.

Even if you are not a Lutheran, your life has been shaped by

the legacy of Martin Luther.

* The notion

of civil rights can be traced back to Luther, and it is no small thing that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. received his namesake from the German monk who stood up against the powers and fought for the value of every human soul.

* Martin Luther also believed that girls should

be educated just as much as boys, an idea that eventually contributed to the women's rights movement (though, admittedly, Luther was by no means a "feminist" in the modern sense of the word).

* The

wave of immigrants into America seeking freedom from religious persecution in

Europe all goes back to the Protestant movement and its aftermath.

* The

notion that individuals can and should read the Bible for themselves and encounter the

living God through those words goes back to Luther, who was the first to

translate the Bible from ancient languages into the common tongue.

And, sadly, World War II can, in part, be traced to Martin Luther. For while he did many positive things, he also said many negative words about the Jewish people. Those words eventually helped fuel Nazi ideology in Germany.

You probably didn’t know that part about how Lutherans

treated Anabaptists or Jews, did you?

But you also may not be aware of the way in which Lutheranism has shaped lives

in a positive way, far beyond its German, European roots.

Lutherans in America have a long history of reaching out to immigrants

and helping them to get settled in their new country. Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services have

helped thousands of foreign people lost, alone and without any assistance in

this country. For example, the church I

served in Media, PA, once took in a family from one of the former Soviet republics. They arranged for furniture for their home,

stocked their kitchen, helped enroll the children in school, and helped to find

the father a job. All with a family who

spoke not a word of English when they arrived.

They weren’t even Christian, let alone Lutheran. They were Muslim. But that didn’t matter. The church responded to the call to help and

today the family is thriving in their new home.

I recently read a story called “Drifting Toward Hope,” in Parade, the Sunday insert in the newspaper, about a man named Vinh Chung and his family who were refugees from Vietnam more than 30 years ago. He tells about escaping Vietnam after the Viet Cong took his family’s rice milling business and forced them to live in poverty. His parents and seven siblings – ten of them in all - set out on a decrepit fishing boat in 1979 with about 83 others, and they got lost on the South China Sea. For five days they drifted without food or water and were beginning to contemplate suicide. Then a World Vision aid ship spotted them and rescued them from certain death. They were eventually brought to Fort Smith, Arkansas, where a Lutheran church sponsored his family’s move to the United States.

Though they had no possessions and could speak no English, the church helped them to get settled in their new country, their new community, and helped to find employment for his father in a fiberglass factory. Vinh says that his time was divided between school, work and church. “Work gave me discipline and kept me out of trouble; church gave me community and a strong faith,” he recalls. “My siblings and I walked a path two inches wide and 18 years long, but it turned out to be a good one.” Today he and his siblings hold a total of six doctorates and five master’s degrees from schools such as Harvard, Yale, Georgetown, and other prestigious Universities.

Eventually Vinh had an opportunity to go back to Vietnam to visit relatives who remained. He was shocked by the poverty. They live in shacks with barely any furniture and hardly enough resources to eke out a living.

And what is more, the very air you breathe, the clean water you

drink, the animals and plants that feed you, the land upon which you home is

situated – none of that was created by you.

You did nothing to deserve this Earth that God created. There is nothing you can do to earn God’s

love and care for you. It simply exists not

because of who you are, but because that is who God is. That is called grace.

Of course, what you do with that blessing is in your

hands. The first and foremost response

for me is to feel gratitude. I am profoundly and humbly grateful to have

received these blessings. And I have to

take time every day when I wake up, every time I sit down to a meal, every time

I receive a paycheck, every time I walk in God’s creation, and . . . even every

time I am ready to rattle off a list of complaints about the life I live. First I must stop and give thanks that I even

have a life to complain about. Giving thanks

puts things into the proper perspective.

Not just during a commercialized holiday next month, but every day,

several times a day, I need to slow down and exist in a state of gratitude.

And then, yes, I need to work diligently to make the most of

what has been entrusted to me. Like one

of the servants given a share of resources in Jesus’ parable of the talents, I

am being held accountable for the treasure that I have been given to steward,

knowing that it was not mine to begin with, nor will it be mine to keep

forever. It all belongs to God, and I

want to be able to hear those words:

Well done, good and faithful servant.

That means if you are a student in school, you do your best

and work diligently to learn all you can, to use your brain and body in the

best way possible, because God has entrusted them to you. And if you are working at a job, you do your

best and work diligently and with the utmost integrity to use your brain and

body in the best way possible, because God has entrusted them to you. If you are raising children, you do your best

and work diligently to keep them fed and clothed and housed and healthy. You treat them with respect, even if they

make you angry. Because they are God’s, not yours, and you must treat

them as God’s treasures entrusted to you.

And if you no longer work full time or raise children full

time, do not think that your days of accountability are over. You are still called on to do your best and

work diligently at whatever your brain and body will still allow you to

do. Maybe that is serving here at the

church, or visiting a sick friend, or making something for someone, or sitting

down with your prayer list and lifting those people to God.

And we are called to pass on that blessing to others. Today, Vinh serves on World Vision’s Board of

Directors, and his book, Where the Wind Leads, has been published. The

blessings bestowed on him, through no merit of his own, he is passing on to

others.

I see youth preparing to serve a spaghetti supper to raise money to go to Detroit next summer to do God’s work with their hands.

I see a member of the Rich Huff fund going out to purchase clothes for a child in need in our area. I see donated food in our narthex that will be taken to Hand Up or Mazeppa Manna to feed our hungry neighbors.

I see people signing up to help serve a meal at St. Andrew’s next month. The list just goes on and on.

We did nothing to deserve the grace that has been bestowed

on us. And we do everything to express

our gratitude and pass on the blessing to others. Thanks be to God for a man whose hands helped

change the world. Thanks be to God for

your hands that are continuing to serve and change the world today.

And thanks be to God for the One who touched

Luther’s life, and yours and mine – Jesus Christ, showing us what it means to give

ourselves fully to God, trusting that grace and mercy for ourselves and the

world. Amen.

Source: Parade, August 10, 2014

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)