A RIVER RUNS THROUGH IT

Sermon Series

The Rev. Leah D. Schade

June 30, 2013 - Part One: Moses in the Bulrushes

First Reading -- Exodus 2:1-10

(Opening/closing line from A River Runs Through It, while draping blue river cloth over pulpit.)

“Eventually all things merge into one. And a river runs through it. The river was cut from the world’s great flood and flows over rocks from the basement of time. On some of the rocks are timeless raindrops. Under the rocks are the words. And some of the words are theirs. I am haunted by waters.”

You may recognize those words from the book and movie, A River Runs Through It. Today we are beginning a five-part sermon series about rivers in the Bible. Summer seems to be a good time to do this. Some of my best summertime and vacation memories have to do with rivers. I grew up in York, not far from the Susquehanna River.

Sermon Series

The Rev. Leah D. Schade

June 30, 2013 - Part One: Moses in the Bulrushes

First Reading -- Exodus 2:1-10

(Opening/closing line from A River Runs Through It, while draping blue river cloth over pulpit.)

“Eventually all things merge into one. And a river runs through it. The river was cut from the world’s great flood and flows over rocks from the basement of time. On some of the rocks are timeless raindrops. Under the rocks are the words. And some of the words are theirs. I am haunted by waters.”

You may recognize those words from the book and movie, A River Runs Through It. Today we are beginning a five-part sermon series about rivers in the Bible. Summer seems to be a good time to do this. Some of my best summertime and vacation memories have to do with rivers. I grew up in York, not far from the Susquehanna River.

I have memories of fishing in a

boat along the river with my father, our time together as unhurried as the

slow-moving current on a warm summer evening.

There is a place near Wrightsville called Long Level, where my Aunt Joan would take me for long walks and talks. I would marvel at the long expanse of the river stretching out in front of me, skipping stones across the tiny waves.

And now since living in Milton along the West Branch of the Susquehanna, I have an even greater love for the river. Last year I helped with a water blessing ceremony at the marina at Shikelammy State Park. And my husband and I take great joy in walking with our children along the river on the island at Milton State Park. I am hoping the create memories for them that will last a lifetime.

The Bible, too, has “river memories”. We’re going to be exploring five of them in this sermon series. After having read through these texts, I’ve come to some conclusions about rivers:

1) Rivers can bring out the best in people.

2) Rivers can bring out the worst in people.

Today we’re going to look at a story where the river brings out the worst and the best in people. The river in this case is the Nile in Egypt, and the story takes place thousands of years ago when the people of Israel were slaves in this powerful desert empire.

The Pharaoh instituted a policy of slavery and apartheid in the land, forcing the Israelites into hard labor. He thought this would put them in their place, teach them who was in control, keep them quiet and submissive.

But even in the midst of this hardship, the Israelites continued to grow in numbers and strength. So Pharaoh responded by imposing more and more harsh tasks upon them. Not only that, but he came up with a plan of genocide. He decreed that the male babies born in Israelite homes should be killed. It made perfect sense. If you kill all the males, then they would not be able to rise up against their oppressors.

Pharaoh made a key mistake, however. He underestimated the power of the women. First of all, he instructed the Egyptian midwives to kill the male babies that were born. Now he should have known better. I was attended to by midwives when I gave birth to Rachel and Benjamin. And I can tell you, there’s no way you could convince these women to kill any child that they helped bring into the world. So when Pharaoh summoned them to ask why they were letting all the male children live, they came up with a very clever answer.

“Because the Hebrew women are not like the Egyptian women; for they are vigorous and give birth before the midwife comes to them.” One of the few times it was okay to tell a lie in the Bible.

So Pharaoh went beyond the midwives and created a law for all the Egyptians, “Every boy that is born to the Hebrews you shall throw into the river Nile.” You see, rivers can bring out the worst in people.

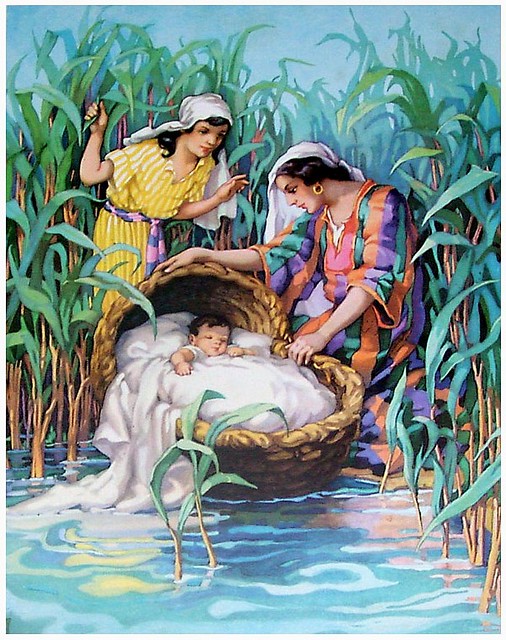

And then we come to this beloved story from Sunday School - Baby Moses in the bulrushes. Being a mother myself I try to imagine what it must have been like for this woman to take her precious three-month old baby, wrap him in a blanket, place him in a basket, and set him floating among the reeds along the river’s edge.

Things would have to be desperate for me to let my child go like this, entrusting him or her to the unpredictable flow of the river, not knowing who might find my baby, and what might happen to him. What could drive a mother to do such a thing?

A friend of mine shared with me a true story about a missionary he met in Africa who was getting ready to board a plane to return to the US. The conditions in Liberia at the time were as bad as they can get - civil war, famine, disease. Just as she was to get on the plane, a woman came up to her, holding out a package wrapped up in a tattered blanket. The missionary saw that it was a child. The mother was begging her to take the baby along home with her, knowing that at least the child would have some chance of survival if she let him go to another. It would be better to entrust her child to the arms of another and suffer the pain of that separation and loss in order that he might live, than to try to keep the child with her, knowing that he will die in her arms.

I can only imagine that kind of dire situation in my worst nightmare. But that is what Moses’ mother faced. Yet even though she was desperate, she thought this through. She was not a stupid woman. She strategically placed her older daughter a little ways off to watch over her little brother. And then Pharaoh’s daughter came with her entourage to bathe in the River Nile. Coincidence? Or had Moses’ mother cleverly planned this out ahead of time? We’ll never know. All the Bible tells us is that Pharaoh’s daughter discovered the basket, undoubtedly hearing the child crying.

She knew right away that this was a Hebrew child. What she should have done - what the law said, what her father would have had her do - was to take that child and throw it out into the river and watch it drown, feeling satisfaction that the only good Israelite is a dead Israelite. You know all those terrible racist jokes that we tell today that undoubtedly had their versions in Egypt. Pharaoh’s daughter could probably hear them in her mind: “What do you call a hundred male Israelite babies at the bottom of the Nile? A good start.” And laughter would erupt from the Egyptian men around her father’s table.

But she could not do it. She knew it was wrong. She knew the law was unjust. She knew that’s not the kind of person she was. She might have been her father’s daughter, but she was not her father’s henchman.

She picked up that baby and held it to her, wondering how she was going to feed this child who was obviously hungry to nurse. And lo and behold, along comes a Hebrew girl who says, “I know of a Hebrew woman who could nurse this child for you.”

Sometimes I wonder if Pharaoh’s daughter might have figured out what was going on. Could she see the resemblance between the mother and the daughter and the baby boy? Again, we’ll never know. But in any case, she gave the boy back to his mother to nurse him and raise him up until he became a young man. Not only that, but she gave money to Moses’ mother to do this. So not only was she saving the life of Moses, she was saving the life of his family as well. Remember - the Israelites were slaves; they were never paid for their work. But Pharaoh’s daughter broke with her father again by paying this woman her wages, honoring her personhood, lifting her up with dignity.

And so you see, once again, Pharaoh underestimated the power of the women. The Bible doesn’t even see fit to give them names, these two Hebrew slaves, and an Egyptian princess. But here they are conspiring together to save the life of one child and his family.

Because, you see, Pharaoh not only underestimated the power of the women, he also underestimated the power of God. Because the river can sometimes bring out the best in people. Pharaoh intended for those waters to be an instrument of death. But God had other plans. God used that Nile River to bring out the best in those women. And at least for this one child, they became the saving waters of life. In fact, the name that Pharaoh’s daughter gave this little boy has a double meaning that shows the little joke she played on her father. The name Moses in Egyptian means “son”. But do you know what it means in Hebrew? The Hebrew word “Mosheh” means, “I drew him out of the water.”

And there is another pun on Moses’ name. The word “Masheh” means “the one who draws out.” Pharaoh’s daughter might have thought of herself as drawing Moses out of the waters and saving his life. But it will be Moses who, as a man, draws out the people of Israel, drawing them out of the Red Sea unharmed, pulling them from slavery in the land of Egypt and bringing them to the Promised Land.

It is an interesting idea - the concept of women conspiring beyond boundaries of race and class to work against unjust laws and practices. And it still happens today.. I think of the organization called Mothers Against Drunk Driving, where the mother of a child who died when a drunk driver hit him, turned her grief into a force for good, educating people about the dangers and immorality of driving after drinking. That organization cuts across different economic and racial lines and has prevented countless death through their efforts. I think, too, of the Million Mom March which brought together mothers and women from across our nation to speak out against gun violence.

It even happens right here in the Susquehanna Valley at the Transitions crisis center where women help other women and their children who are victims of domestic abuse. It’s women coming together across the boundaries of race and class to save and protect their children.

It might have even happened in your household. I’ll bet some of you were raised without a father in the house, for whatever reason - divorce, death, or just not being there. And who was it that looked after you, and put a roof over your head, and made sure you had something to eat, and disciplined you when you were acting up. It was your mother . . . or your grandmother . . . or your sister . . . or your aunt. It’s that way in a lot of families. When the chips are down and the men are violent or neglectful or just not there, the women come together to make sure the children will survive. Sometimes they have to use subversive means, pool their resources, do whatever they have to do to survive. But they do it. They draw the children out of dangerous waters.

This is not to say that all women are heroes, for there are certainly some mothers who have committed abuse. But if you think about your life, you can probably name at least one woman who demonstrated that kind of strength and cunning and love that those women had at the Nile River had which helped to save you from a time of danger. Who was the woman who drew you out of the dangerous water? Have you thanked her? Have you lived your life to carry on her legacy? Have you made her proud of you? Are you following in her footsteps, helping to pull others out of dangerous waters?

Because the river is a metaphor for life. Life can sometimes bring out the best in people and sometimes bring out the worst. Think of that river of life and what God is calling you to do. How will the river - how will God bring out the best in you?

There is a place near Wrightsville called Long Level, where my Aunt Joan would take me for long walks and talks. I would marvel at the long expanse of the river stretching out in front of me, skipping stones across the tiny waves.

And now since living in Milton along the West Branch of the Susquehanna, I have an even greater love for the river. Last year I helped with a water blessing ceremony at the marina at Shikelammy State Park. And my husband and I take great joy in walking with our children along the river on the island at Milton State Park. I am hoping the create memories for them that will last a lifetime.

The Bible, too, has “river memories”. We’re going to be exploring five of them in this sermon series. After having read through these texts, I’ve come to some conclusions about rivers:

1) Rivers can bring out the best in people.

2) Rivers can bring out the worst in people.

Today we’re going to look at a story where the river brings out the worst and the best in people. The river in this case is the Nile in Egypt, and the story takes place thousands of years ago when the people of Israel were slaves in this powerful desert empire.

The Pharaoh instituted a policy of slavery and apartheid in the land, forcing the Israelites into hard labor. He thought this would put them in their place, teach them who was in control, keep them quiet and submissive.

But even in the midst of this hardship, the Israelites continued to grow in numbers and strength. So Pharaoh responded by imposing more and more harsh tasks upon them. Not only that, but he came up with a plan of genocide. He decreed that the male babies born in Israelite homes should be killed. It made perfect sense. If you kill all the males, then they would not be able to rise up against their oppressors.

Pharaoh made a key mistake, however. He underestimated the power of the women. First of all, he instructed the Egyptian midwives to kill the male babies that were born. Now he should have known better. I was attended to by midwives when I gave birth to Rachel and Benjamin. And I can tell you, there’s no way you could convince these women to kill any child that they helped bring into the world. So when Pharaoh summoned them to ask why they were letting all the male children live, they came up with a very clever answer.

“Because the Hebrew women are not like the Egyptian women; for they are vigorous and give birth before the midwife comes to them.” One of the few times it was okay to tell a lie in the Bible.

So Pharaoh went beyond the midwives and created a law for all the Egyptians, “Every boy that is born to the Hebrews you shall throw into the river Nile.” You see, rivers can bring out the worst in people.

And then we come to this beloved story from Sunday School - Baby Moses in the bulrushes. Being a mother myself I try to imagine what it must have been like for this woman to take her precious three-month old baby, wrap him in a blanket, place him in a basket, and set him floating among the reeds along the river’s edge.

Things would have to be desperate for me to let my child go like this, entrusting him or her to the unpredictable flow of the river, not knowing who might find my baby, and what might happen to him. What could drive a mother to do such a thing?

A friend of mine shared with me a true story about a missionary he met in Africa who was getting ready to board a plane to return to the US. The conditions in Liberia at the time were as bad as they can get - civil war, famine, disease. Just as she was to get on the plane, a woman came up to her, holding out a package wrapped up in a tattered blanket. The missionary saw that it was a child. The mother was begging her to take the baby along home with her, knowing that at least the child would have some chance of survival if she let him go to another. It would be better to entrust her child to the arms of another and suffer the pain of that separation and loss in order that he might live, than to try to keep the child with her, knowing that he will die in her arms.

I can only imagine that kind of dire situation in my worst nightmare. But that is what Moses’ mother faced. Yet even though she was desperate, she thought this through. She was not a stupid woman. She strategically placed her older daughter a little ways off to watch over her little brother. And then Pharaoh’s daughter came with her entourage to bathe in the River Nile. Coincidence? Or had Moses’ mother cleverly planned this out ahead of time? We’ll never know. All the Bible tells us is that Pharaoh’s daughter discovered the basket, undoubtedly hearing the child crying.

She knew right away that this was a Hebrew child. What she should have done - what the law said, what her father would have had her do - was to take that child and throw it out into the river and watch it drown, feeling satisfaction that the only good Israelite is a dead Israelite. You know all those terrible racist jokes that we tell today that undoubtedly had their versions in Egypt. Pharaoh’s daughter could probably hear them in her mind: “What do you call a hundred male Israelite babies at the bottom of the Nile? A good start.” And laughter would erupt from the Egyptian men around her father’s table.

But she could not do it. She knew it was wrong. She knew the law was unjust. She knew that’s not the kind of person she was. She might have been her father’s daughter, but she was not her father’s henchman.

She picked up that baby and held it to her, wondering how she was going to feed this child who was obviously hungry to nurse. And lo and behold, along comes a Hebrew girl who says, “I know of a Hebrew woman who could nurse this child for you.”

Sometimes I wonder if Pharaoh’s daughter might have figured out what was going on. Could she see the resemblance between the mother and the daughter and the baby boy? Again, we’ll never know. But in any case, she gave the boy back to his mother to nurse him and raise him up until he became a young man. Not only that, but she gave money to Moses’ mother to do this. So not only was she saving the life of Moses, she was saving the life of his family as well. Remember - the Israelites were slaves; they were never paid for their work. But Pharaoh’s daughter broke with her father again by paying this woman her wages, honoring her personhood, lifting her up with dignity.

And so you see, once again, Pharaoh underestimated the power of the women. The Bible doesn’t even see fit to give them names, these two Hebrew slaves, and an Egyptian princess. But here they are conspiring together to save the life of one child and his family.

Because, you see, Pharaoh not only underestimated the power of the women, he also underestimated the power of God. Because the river can sometimes bring out the best in people. Pharaoh intended for those waters to be an instrument of death. But God had other plans. God used that Nile River to bring out the best in those women. And at least for this one child, they became the saving waters of life. In fact, the name that Pharaoh’s daughter gave this little boy has a double meaning that shows the little joke she played on her father. The name Moses in Egyptian means “son”. But do you know what it means in Hebrew? The Hebrew word “Mosheh” means, “I drew him out of the water.”

And there is another pun on Moses’ name. The word “Masheh” means “the one who draws out.” Pharaoh’s daughter might have thought of herself as drawing Moses out of the waters and saving his life. But it will be Moses who, as a man, draws out the people of Israel, drawing them out of the Red Sea unharmed, pulling them from slavery in the land of Egypt and bringing them to the Promised Land.

It is an interesting idea - the concept of women conspiring beyond boundaries of race and class to work against unjust laws and practices. And it still happens today.. I think of the organization called Mothers Against Drunk Driving, where the mother of a child who died when a drunk driver hit him, turned her grief into a force for good, educating people about the dangers and immorality of driving after drinking. That organization cuts across different economic and racial lines and has prevented countless death through their efforts. I think, too, of the Million Mom March which brought together mothers and women from across our nation to speak out against gun violence.

It even happens right here in the Susquehanna Valley at the Transitions crisis center where women help other women and their children who are victims of domestic abuse. It’s women coming together across the boundaries of race and class to save and protect their children.

It might have even happened in your household. I’ll bet some of you were raised without a father in the house, for whatever reason - divorce, death, or just not being there. And who was it that looked after you, and put a roof over your head, and made sure you had something to eat, and disciplined you when you were acting up. It was your mother . . . or your grandmother . . . or your sister . . . or your aunt. It’s that way in a lot of families. When the chips are down and the men are violent or neglectful or just not there, the women come together to make sure the children will survive. Sometimes they have to use subversive means, pool their resources, do whatever they have to do to survive. But they do it. They draw the children out of dangerous waters.

This is not to say that all women are heroes, for there are certainly some mothers who have committed abuse. But if you think about your life, you can probably name at least one woman who demonstrated that kind of strength and cunning and love that those women had at the Nile River had which helped to save you from a time of danger. Who was the woman who drew you out of the dangerous water? Have you thanked her? Have you lived your life to carry on her legacy? Have you made her proud of you? Are you following in her footsteps, helping to pull others out of dangerous waters?

Because the river is a metaphor for life. Life can sometimes bring out the best in people and sometimes bring out the worst. Think of that river of life and what God is calling you to do. How will the river - how will God bring out the best in you?

Amen.